The Treaty on the Ground by Rachael Bell

Author:Rachael Bell [Bell, Rachael]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780994130051

Barnesnoble:

Publisher: Massey University Press

Published: 2017-01-01T00:00:00+00:00

UNCONDITIONAL RATHER THAN RECIPROCAL

THE TREATY AND THE STATE SECTOR

Kim Workman (NgÄti Kahungunu ki Wairarapa me RangitÄne o Wairarapa), Adjunct Research Associate, Institute of Criminology, Victoria University of Wellington

In the 1980s, building on the establishment of the Waitangi Tribunal in 1975, government began responding to MÄori demands: it expanded the powers of the Waitangi Tribunal, increasingly and controversially included references to the Treaty of Waitangi in legislation, and looked to devolve responsibilities for a wide range of services to iwi organisations. During this period of dramatic state-sector reform, biculturalism provided a model, and the Treaty of Waitangi became the primary platform for reform.

The development activity of the 1980s was preceded by a period of considerable political upheaval in the 1970s. In the latter part of that decade, the anti-war movement merged with other major causes: womenâs rights, the anti-apartheid movement and the emerging MÄori renaissance. MÄori sought increased control over their own affairs; between 1975 and 1980 there were high-profile protests against the alienation of MÄori land, and powerful resistance against earlier policies of assimilation and integration.

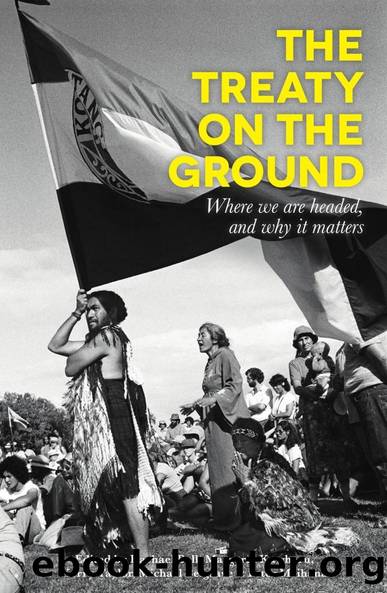

The continued alienation of MÄori land was met with confrontational expressions of rangatiratanga at Waitangi Day and a succession of protests: the 1975 hÄ«koi led by Te Rarawa leader Whina Cooper,1 the occupation of Bastion Point in 1977, and the Raglan Golf Course protest in 1978. MÄori made clear its autonomist view of MÄori partnership with the Crown, and called for the government to reflect the bicultural direction of New Zealand society.

NgÄ Tamatoa was in ascendance in the 1970s and, according to historian Richard Hill, by the early 1980s the Waitangi Action Committee was referred to as being at the âradical cutting edge of MÄori politicsâ both in its methods and demands.2 While they earned the ire of conservative MÄori leadership and the Muldoon Government, protestors were able to draw upon support, not only from conservative MÄori leaders, but also from increasing numbers of PÄkehÄ who identified with, or participated in, MÄori activist causes.

When a new political party, Mana Motuhake, was formed in 1980, it made clear its autonomist view of MÄori sovereignty, but at the same time called on the government to reflect the bicultural direction of New Zealand society. This approach earned support outside the party, including from within the ranks of the public service. It was able to pull together a range of ideas and thoughts that reflected the need to identify and repair past harm, and then face the future with confidence. It rejected the assimilationist policies of the previous governments and demanded reparation for past breaches of the Treaty. Its message for the future was one of hope, self-reliance and advancement. Mana Motuhakeâs influence was considerable, and complemented the Treaty-based discourse which increasingly came to permeate the public and political discussion, moving the debate beyond that of traditional concern with land issues to include the discussion about the place of MÄori culture in a bicultural society and how rangatiratanga could be integrated into existing constitutional and political arrangements.3 The Hunn-styled policies of assimilation and/or integration were over.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Five People You Meet in Heaven by Mitch Albom(3550)

The Secret Power of Speaking God's Word by Joyce Meyer(3164)

Real Sex by Lauren F. Winner(3006)

Name Book, The: Over 10,000 Names--Their Meanings, Origins, and Spiritual Significance by Astoria Dorothy(2972)

The Holy Spirit by Billy Graham(2939)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2842)

How The Mind Works by Steven Pinker(2811)

ESV Study Bible by Crossway(2772)

Ancient Worlds by Michael Scott(2678)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2576)

The Meaning of the Library by unknow(2563)

The ESV Study Bible by Crossway Bibles(2546)

The Gnostic Gospels by Pagels Elaine(2518)

MOSES THE EGYPTIAN by Jan Assmann(2411)

Jesus by Paul Johnson(2351)

City of Stairs by Robert Jackson Bennett(2339)

The Complete Dead Sea Scrolls in English (7th Edition) (Penguin Classics) by Geza Vermes(2269)

The Nativity by Geza Vermes(2226)

Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament by John H. Walton(2220)